Just like grammar used to make

The way I see language

Welcome, aspiring polyglot! Once per week at minimum I find myself ranting to a student that grammar is a waste of time. While conventional schools spend years going over one or two verb tenses, my preference is to cover 6-8 of them in the first month of class. The reason behind this is simple. Even if you don’t understand or master a verb tense, over time they will become more and more clear through use and context clues. At first it’s frustrating, sure, but it quickly becomes a powerful tool in your linguistic utility belt.

Verbs, adjectives, and nouns

One of the ways we do this is by focusing on the patterns in different languages that can and should be used to learn multiple words while working on your grammar structures. Take, for example, the Spanish word “poder” or the French word “pouvoir”. They are both verbs for “to can” or “to be able to”, but they are also both nouns for “power”, as in having the power to be able to do something.

These verbs can be further extrapolated into people who do the things by adding the appropriate endings. Now, this doesn’t work every time, but if you only do things that work 100% of the time you are going to spend a lot of time sitting in silence. These 80/20 and 90/10 wins are what you should be using to build your confidence while fleshing out the last 10-20%. In fact, if you do this right you can even make progress while watching Dora the Explorer.

I like using Dora as an example with my students because it’s nearly universally known and it provides the perfect example that can be used over and over and over again. Dora is an explorer. In English, to delineate someone who does something, we typically add the suffix “-er”, explor-er, for example. Spanish has a similar mechanism that is “-ador(a)” depending on the gender. Therefore, Dora is an explor-adora, coming from the Spanish word for explore, explorar.

So in Spanish you can be an explorador (explorer), a jugador (player), a cazador (hunter), and in French you can be a coiffeur (hair cutter, from the verb se coiffer), danseur (dancer), and there are many, many more. But this ending is far from the only way you can maximize your verb time. One of the other things that remains standardized from English to and across romance languages.

If you don’t know what a past participle is and you are learning English or any romance language, you need to understand them. For all intents and purposes, most English past participles (pps) have -ed. That’s how I explain it to my students, at least, pretty hard to forget that! In Spanish they are mostly recognizable by their “-ado” or “-ido” ending; and in French most of the time they will end in “-é”.

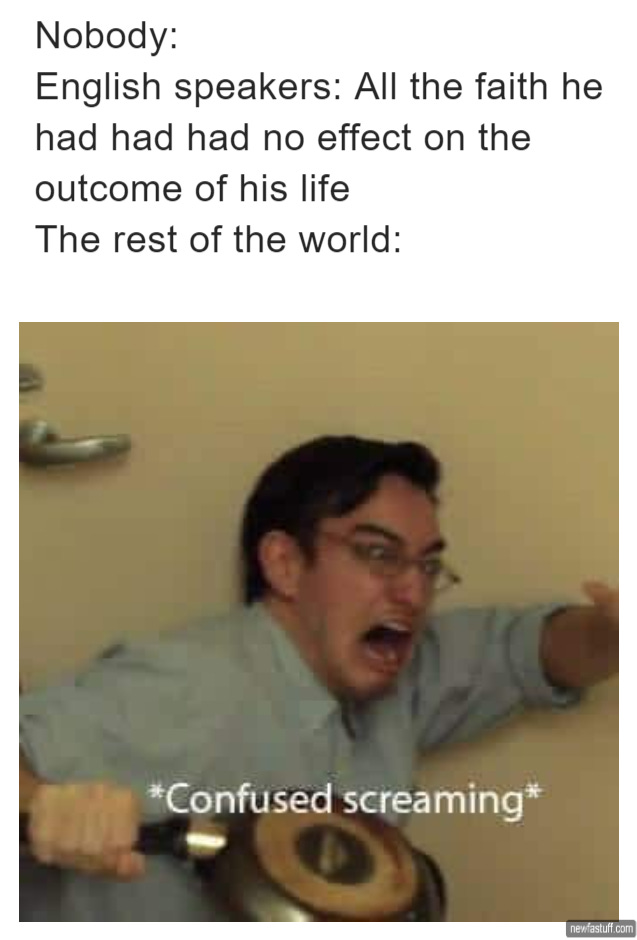

These are used in conjunction with the auxiliary verb “have” in English, “avoir” in French, and “haber” in Spanish. Of these three, only Spanish has a different word for the auxiliary and the action verbs “have”. This means you have to understand the grammar well enough to know which “have” is required in a given context. To put it simply, this auxiliary verb is why we can form the sentence “I have had” in English. The “had” here is the action verb “to have”, it’s past participle (pp) and the “have” here is the present tense conjugation of the auxiliary verb “have”.

Irrespective of the language, these past participles will can be used as descriptive words OR in conjunction with the auxiliary verb in any tense. A well travelled path. Three baked potatoes. His fully lived life. Of course, English has irregulars as well, meaning you need to keep in mind the “pps have -ed” rule is more of a guideline, as with all rules in languages. Two of the most commonly used are the pp for “to make” and “to do” which are “made” and “done” respectively.

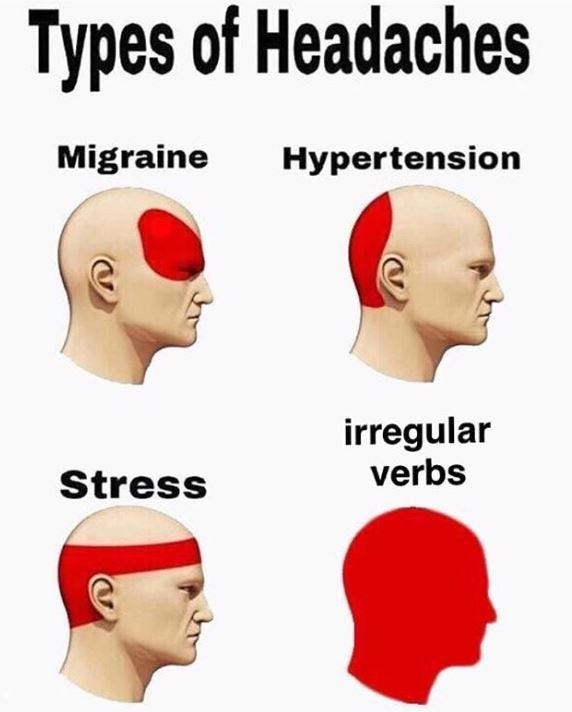

Irregulars

Fortunately, many of the verbs that are irregular in one language are irregular in others. Knowing this means you can move forward making educated guesses on which words may or may not have irregulars waiting for you. This is particularly potent pertaining to past participles. Not only because the pps are equally irregular, but because a few of them provide not only verb tenses and adjectives, but nouns as well.

To make and to do are the same verb in several languages. So, let’s take the Spanish as an example. Hacer is your verb for to make or to do. It is irregular in every tense, similar to English, and the past participle is no exception. In this case it is “hecho”. Therefore, something can be “bien hecho” or well done, but something can also be un hecho or a fact. After all, something that is made or done is, essentially, a fact.

Common bases

The last thing we touch on in my classes with regards to verb tenses are the ways in which you can take advantage of what you already know to extrapolate it to other verbs and tenses. Take the verb Tener. It means “to have” right? Sure, but let’s pretend for one second that instead of to have it’s just “tain” Suddenly we get: obtener or obtain, sostener or sustain, atener or attain, retener or retain, contener or contain.

And, in the words of the late Billy Mayes, but wait there’s more! All of these, thanks to the tener root, are IRREGULARLY conjugated THE SAME. So, ob-tengo, sos-tienes, a-tiene, re-tenemos, con-tienen. And not just in the present tense. Even the future tense and past tense root changes are identical.

Future: ob-tendré, sos-tendrás, a-tendrá, re-tendremos, con-tedrán.

Past: ob-tuve, sos-tuviste, a-tuvo, re-tuvimos, con-tuvieron.

PPs: tener → tenido, ob-tenido, sos-tenido, a-tenido, re-tenido, contenido.

Knowing this can help you understand the difference between the emotion “content” or “contento” in Spanish and the noun “content” or “contenido” in Spanish. Some of these are false friends, but the pattern works because of the tener, not the translation. Poner is another powerful one that can give you tons of vocabulary in simply identifying the patterns.

If you can reframe “poner” which most people are taught is conjugated as “to put/place” as “to pose” something somewhere, your opportunities open up quite a lot. For example, poner (pose), o-poner (oppose), su-poner (suppose), pro-poner (propose), com-poner (compose). Now, let’s look at our pps! Poner becomes puesto, oponer becomes opuesto, suponer becomes supuesto, proponer becomes propuesto and componer becomes compuesto.

Conclusion

Grammar is by far my least favorite part of learning a new language. I suppose that is the reason why I feel the need to learn and understand it so deeply. By learning the grammar of your native language you will noticeably cut down on the time you are forced to deal with grammar in each subsequent language. Taking advantage of the patterns inherent within languages will make things move even quicker, which is always good in my opinion.

There is no way around verb tenses. You don’t have to spend weeks or months mastering them, though. In fact, waiting until something is mastered to start using it will hold you back indefinitely. These strategies have helped many enhance and accelerate their language acquisition; and they will help you, too. It will be difficult, but you can do difficult things and be great. So get out and do some difficult things and become great. I am rooting for you.

Requests

If you have anything you would like covered you can reach out to me on X, Instagram, or at odin@secondlanguagestrategies.com.

Additional Resources

Don’t want to spend time playing catch up? Pick up the 3 Months to Conversational book now available on Amazon! 3 Months to Conversational

For more long form content be sure to check out the website and the FREE Language Learning PDFs we have available!

Subscribe for new content on YouTube and TikTok!

Learning Spanish? We have begun aggregating resources in you Spanish Resource Newsletter!

Don’t forget to pick up your very own French Language Logbook or Spanish Language Logbook